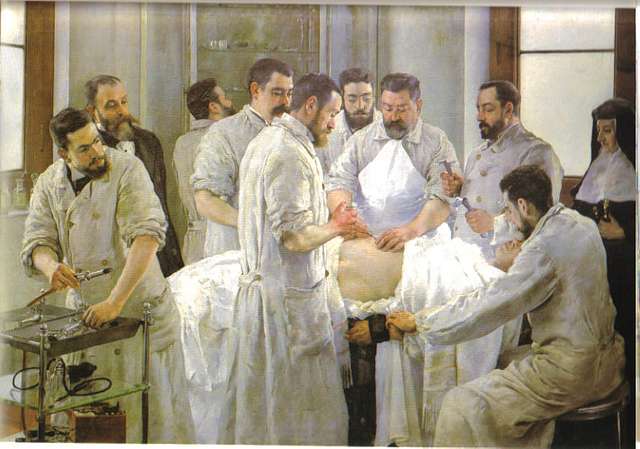

Ignaz Semmelweis (1818 – 1865) was a Hungarian physician.

He noticed that there was a big difference in the mortality rates of women who gave birth in the hospital's two maternity wards. The first ward, staffed by doctors and medical students, had a significantly higher incidence of dangerous childbed fever compared to the second ward, where midwives attended to the births.

After investigating the difference, Semmelweis concluded that the high mortality rate in the first ward was due to contaminated hands of the medical staff. He hypothesized that they were carrying infectious material from autopsies to the birthing mothers, leading to infections. Semmelweis implemented a simple yet groundbreaking solution. He introduced a chlorinated solution to disinfect the hands of the medical staff before attending to births. This handwashing led to a dramatic decrease in the incidence of childbed fever in the first ward - and many lives saved. This confirmed Semmelweis's theory that hand hygiene was crucial in preventing the spread of infectious diseases.

Despite the success of his intervention, Semmelweis faced opposition and ridicule from the medical community of his time. The weight of authority stood against his teachings. His colleagues simply would not admit that they were wrong and that they were the ones responsible for the deaths by means of their unwashed hands. He addressed several open letters to professors of medicine in other countries but to little effect. His letters grew increasingly offensive, with expressions of anger, frustration, and bitterness. The years of controversy had gradually undermined his spirit, and he suffered bouts of severe depression. By 1865 his behaviour had become increasingly erratic (possibly with a contribution of dementia or syphilis too). His colleagues eventually lured him into visiting a mental institution. Upon arrival there, Semmelweis, realizing his colleagues’ intent, protested and attempted to leave but was taken in by the guards. He was beaten severely, placed under confinement, and subjected to treatments with castor oil. He died two weeks into his detention at the asylum under unclear circumstances.

His work was not appreciated during his lifetime.

However, after his death, his contributions to infection control and aseptic practices have had a lasting impact on modern medicine. He is now recognized as a pioneer in public health and is credited with laying the foundation for aseptic techniques that are standard in healthcare today.

Semmelweis reflex: The tendency to reject new evidence, new knowledge because it contradicts established norms, beliefs or paradigms.

Have you ever heard of lobotomy? Something about sticking a needle in someone’s head to "calm them down"? For a few decades, this brutal and horrifying method of damaging someone’s brain was widely used as an actual treatment for mental illness. Yes, medical professionals, praised as experts, once believed that drilling into the skull and cutting the connections in the frontal lobe - the part of the brain responsible for decision-making, personality, social behavior - would somehow “fix” people suffering from depression, anxiety, schizophrenia or simply being “difficult.” Let that sink in: they mutilated people’s brains because they didn’t know how to help them. And what’s worse, it wasn’t just fringe doctors doing this in basements - lobotomy was mainstream. It was promoted in top hospitals, celebrated by the media, and even awarded a Nobel Prize. That’s right - António Egas Moniz received the Nobel Prize for inventing a procedure that destroyed countless lives. Sure, he probably had very good intentions and just wanted to help. But what difference does it make? Many of the lobotomized were not even psychotic or dangerous - just women with postpartum depression, teenagers with mood issues, war veterans with trauma, or patients who simply didn’t improve fast enough as doctors hoped for. And rather than admit the limits of their knowledge or admit failure, the medical system doubled down, institutionalized these people, and then destroyed the very parts of them that made them them.

And guess what? For years, pretty much no one dared question it. Why? Because questioning it would mean challenging the entire medical hierarchy, the “science” of the day, the reputation of professors and prize winners. The very definition of the Semmelweis reflex - new evidence or skepticism was outright rejected because it didn’t fit the existing paradigm. So instead of pausing and reevaluating, they went on blindingly - until it was far too late for thousands.

But wait — it gets even weirder: Masturbation causing epilepsy?

History offers plenty more examples. It sounds absurd today, but for well over a century - especially from the late 1700s through the 1800s - a significant portion of medical and moral authorities seriously believed that masturbation could cause epilepsy, along with insanity, blindness, weakness, and even early death.

One influential source was the 1712 pamphlet Onania, which helped spread panic over “self-abuse.” Later, prominent figures like Swiss physician Samuel-Auguste Tissot argued that semen loss through masturbation weakened the body and brain, and could lead to neurological disorders - including seizures. These ideas were taken seriously in medical circles throughout the 18th and 19th centuries (!).

So instead of admitting they didn’t know what caused epilepsy - which, at the time, was mysterious and poorly understood - many doctors blamed sexuality. And this wasn’t harmless advice. Treatments ranged from enforced celibacy and cold showers to circumcision or clitoridectomy - done not to heal, but to stop the behavior. People were mutilated or shamed for a behavior that was both normal and unrelated to the illness in question. All because medicine couldn’t say “We don’t know yet.”

What is the nature of the current medical system (and of society itself)? Is it really different from Semmelweis's times?

Perhaps some of the current medical interventions, dogmas and approaches that are considered normal, logical, advanced or seemingly self-evident, ones that medical professionals automatically follow, are not such at all when scrutinized a bit more closely?

Why is it that, instead of simply admitting they don’t know what’s wrong, that they may have misdiagnosed the patient or that the treatment simply isn’t working, so many doctors choose to double down - they blame the patient, clinging to a narrative, all to protect the illusion that they’re still in control?

ME/CFS, long covid and many other examples come in handy here.

What if many diagnoses that today’s conventional medicine labels as incurable - or doesn’t even acknowledge - are actually curable, or at least more manageable, when viewed through a different lens? For example, when integrative approaches that consider the gut microbiome, diet or whatever else and "alternative" therapies are applied? Or you know, simply when the latest scientific knowledge is actually taken into account? Too much to ask for, I guess.